Archive

The Paradox of Progress: Technology, Penmanship, and the Authenticity of Writing

The relentless march of technological advancement has undeniably revolutionized education, offering students unprecedented access to information and tools. Yet, this progress has inadvertently created a paradoxical challenge: a decline in penmanship among students, even as the demand for legible handwriting resurfaces in the age of artificial intelligence. From the observation of my own students, ranging from middle school to high school, to the increasing prevalence of typing practice over handwriting in younger children, it is evident that the art of crafting letters by hand is waning. This trend, however, clashes starkly with the evolving landscape of college admissions, where institutions are increasingly emphasizing authentic, on-the-spot writing skills as a countermeasure to AI-generated content.

The digital age has fostered a culture where typing and digital communication reign supreme. Students are adept at navigating keyboards and touchscreens, but the physical act of writing with a pen or pencil seems to be falling by the wayside. This is particularly concerning given the cognitive benefits associated with handwriting, including improved memory, fine motor skills, and creative thinking. Yet, the emphasis on digital literacy in early education, exemplified by my 6th-grade niece’s focus on typing, reflects a broader societal shift towards prioritizing technological proficiency.

Ironically, as AI tools become increasingly sophisticated, institutions of higher learning are recognizing the need to reassert the value of authentic, human-generated work. The surge in AI-assisted writing has prompted many elite colleges and universities to implement new evaluation methods that prioritize spontaneous, handwritten responses. This shift is not a regression, but rather an adaptation to ensure that students possess genuine critical thinking and communication skills, qualities that remain uniquely human.

Institutions like MIT, Georgetown, and the University of California system have begun incorporating timed writing assessments, maker portfolios, and spontaneous response questions into their application processes. These methods are designed to assess a student’s ability to think critically and express themselves clearly under pressure, without the aid of pre-prepared or AI-generated content. For example, Yale University’s use of video response questions and the University of Chicago’s reliance on unexpected creative prompts during interviews push applicants to engage with material in real-time, revealing their genuine intellectual agility.

The implementation of these methods is a testament to the recognition that AI, while a powerful tool, cannot replicate the nuanced expression of human thought and creativity. The ability to articulate ideas coherently and legibly, especially under time constraints, is a crucial skill that transcends technological fluency. The emphasis on legible handwriting, in particular, speaks to a desire for authenticity and a return to the fundamentals of communication. While AI can generate text, it cannot replicate the personal touch and immediate expression conveyed through handwritten words.

This evolution in college admissions is not merely a reactionary measure against AI; it is a proactive step towards ensuring that students develop the essential skills needed to thrive in an increasingly complex world. It is a reminder that while technology can enhance learning, it should not replace the foundational skills that underpin effective communication. The ability to write legibly, think critically, and express oneself authentically are qualities that will remain invaluable, regardless of technological advancements.

As technology continues to reshape education, it is imperative that we strike a balance between digital literacy and the fundamental skills that define human communication. Colleges and universities are leading the charge in this endeavor, adapting their evaluation methods to ensure that students possess the critical thinking and writing abilities needed to succeed. The future of education lies not in choosing between technology and tradition, but in finding a harmonious integration that fosters both innovation and authenticity.

After AP Cal BC – Take Advanced Mathematics in the Age of A.I.

By James H. Choi

http://Column.SabioAcademy.com

Source URL

Only a small percentage of American high school students complete AP Calculus BC. As of 2024, about 87,000 students nationwide took this exam, representing just 3% of the approximately 3 million American high school graduates each year.

Mathematics Learning Paths for the AI Era

Students who complete AP Calculus BC before 12th grade now have more diverse options. In today’s AI-dominated era, conceptual understanding and application skills have become more important than calculation abilities, making various learning paths worth considering.

Advanced Data Science and Statistics

If you haven’t taken AP Statistics yet, you should. In the AI era, data interpretation skills are essential, with statistics forming the foundation. Bayesian statistics provides a framework for dealing with uncertainty, while experimental design teaches methodologies for obtaining meaningful results. Data mining techniques help discover patterns in large volumes of data.

It’s important to apply theoretical knowledge through real dataset analysis. Understanding concepts like hypothesis testing, confidence intervals, and regression analysis builds the foundation for data-driven decision making.

Concurrent Learning of Multivariable Calculus and Linear Algebra

Traditionally, students learned Multivariable Calculus before Linear Algebra. However, in the AI era, studying these subjects concurrently is advantageous. Gradient Descent, fundamental to deep learning algorithms, is a core concept in multivariable calculus, while neural network weight updates use matrix operations from linear algebra.

In computer vision, both fields are necessary when representing images as matrices. In natural language processing, techniques like word embeddings utilize vector spaces, requiring understanding of both vector operations and multivariable functions. Understanding optimization problems in machine learning requires comprehensive knowledge of both fields.

Discrete Mathematics and Algorithm Theory

Discrete Mathematics, previously important only to pure mathematics or computer science majors, is now essential for all STEM students. Graph theory forms the basis for applications like social network analysis, recommendation systems, and finding optimal paths. Combinatorics helps understand the decision space of AI systems.

Algorithm analysis provides a framework for evaluating efficiency and complexity, essential for optimizing AI performance. Boolean algebra and logic help understand decision processes and rule-based reasoning. Discrete probability theory forms the basis for AI models dealing with uncertainty, while information theory addresses entropy, a core concept in data compression and machine learning.

Computational Thinking and Programming

Beyond mathematical concepts, developing implementation skills in programming languages is important. Python is suitable for practicing mathematical concepts with its rich libraries for data analysis and machine learning. R is specialized for statistical analysis, while Julia is optimized for numerical computation.

“Computational Thinking” or “Mathematical Computing” courses teach how to decompose mathematical problems algorithmically and implement them in code. Coding matrix operations, numerical solutions of differential equations, and probability simulations helps connect theory and practice.

Practical Approaches

Modern mathematics learning requires balance between theory and practical application:

Project-Based Learning: Solving real problems using AI tools is effective. After learning differential equations, coding physics simulations (like pendulum motion or population growth models) applies theoretical concepts. Applying optimization algorithms to scheduling or resource allocation problems demonstrates practical applications. Analyzing real datasets builds data analysis skills.

Collaboration with AI Tools: Tools like ChatGPT, Wolfram Alpha, and GitHub Copilot should be collaborative partners for concept understanding and problem-solving. Wolfram Alpha helps verify visualizations and step-by-step solutions. ChatGPT provides various explanations to develop understanding. GitHub Copilot teaches different approaches to implementing algorithms. Critically reviewing these tools’ solutions deepens understanding.

Interdisciplinary Applications: Apply mathematics to physics, economics, biology, and social sciences. Physics uses differential equations to model natural phenomena. Economics applies game theory and optimization to decision-making. Biology uses probability theory and differential equations in population genetics and ecosystem modeling. Social sciences employ network theory and statistical methods to understand interactions and behavioral patterns.

Developing Mathematical Intuition: While AI performs calculations instantly, mathematical intuition and creative problem-solving remain uniquely human. Focus on the ‘why’ and ‘how’ to understand fundamental reasons and connections. Try different approaches to problems to develop varied perspectives. Focus on recognizing patterns and generalizing rather than memorizing techniques. Find counterexamples and consider extreme cases to explore theoretical limits. Visual representations strengthen intuitive understanding.

College and Career Preparation

Students who finish AP Calculus BC early can take courses at nearby colleges or through online platforms like edX, Coursera, and Khan Academy. Programs like Stanford’s “Math Camp,” MIT’s “PRIMES,” and Johns Hopkins’ “Center for Talented Youth” offer college-level mathematics experience. “Mathematical Modeling Competitions” and “Algorithm Competitions” develop problem-solving abilities.

Self-directed learning resources include MIT’s OpenCourseWare, Stanford’s online advanced mathematics courses, and Khan Academy. Programs like Coursera’s “Machine Learning” or edX’s “Data Science MicroMasters” apply mathematical knowledge to AI and data science.

For research experience, connect with professors or research institutes for internship opportunities. Many universities offer summer research programs for high school students.

In the AI era, mathematical modeling, algorithmic thinking, and creative application of mathematics are more important than calculation abilities. Designing learning paths to develop these competencies maintains competitiveness as AI technology advances. Mathematical intuition and creative problem-solving are uniquely human strengths that AI cannot easily replace.

Education and Technology

By James H. Choi

http://Column.SabioAcademy.com

Source URL

If we look back at history for a moment, the introduction of technology in education began with the invention of Gutenberg’s printing press. Before that publishing revolution, all books were naturally handwritten and passed down, and I read that one copy of a book written that way was worth $30,000 today. The way to mass-produce these expensive books was “reading and dictation.” In other words, one person would read the contents of the book out loud in front of the classroom, and the students sitting together would write it down. This “reading” is “Lectio” in Latin, which became “Lecture” in English, and we translate it as “lecture,” but its original meaning is “reading.” Even now, if you look at the classrooms where we go to hear “lectures,” you can see that they still maintain the medieval “reading and dictation” method.

In other words, the introduction of the first technology related to education only helped to widely distribute books, but did not change the form of knowledge transmission. Of course, it was a big change that books became cheaper, making it possible for individuals to own them and learn on their own using them. However, most students still spend more time sitting in the classroom, taking notes, without asking questions, even when lectures are indistinguishable from reading aloud. The next revolutionary technology was videotape. Since recording allowed lectures to be played back across time and place, it seemed like it would bring about a revolutionary change in education, but this also only had a small impact in a few fields such as cooking and aerobics, and did not bring about any change in education overall. Although videos could convey more information efficiently than books (think of learning how to disassemble/assemble an engine by reading text), both videos and books were one-way transmission media, so they had limitations in changing the education system. The DVDs that came out later were the same, except with higher resolution.

The next technology is computer-based education, which is where we are today. Now, it is strange to not have computers in schools, but learning the knowledge/concepts embedded in computers began in the 1980s. The reason why this decades-old educational method has become mainstream these days is because it has become cheaper and easier to distribute, has become smaller and more portable, and the development of the Internet has made group collaboration possible. And because its performance has improved, it has become smarter and has begun to take on some of the role of a teacher. For example, in math, even if the problem is not multiple choice, if the answer is a+b/2, it can be graded as b/2+a or (2a+b)/2. In addition, it has become possible to know when, what, and how students studied, record it, and even report it to teachers/parents, which is the first time in history that the conflicting hopes of “cheaper and more detailed student study” can be met at the same time.

This revolution is finally changing the “reading + dictation” education format with the powerful technology that allows two-way information exchange. On the one hand, online university lectures are appearing, and on the other hand, opposition is rising that can be summarized as “Education is definitely about teachers and students meeting face to face and discussing…” At the same time, the question is being raised, “Is it right for the winner-takes-all system to reach the education sector?” The future is unpredictable, but I think that computers will now take center stage in education and change everything around them. How should our children prepare for this unprecedented world? Ironically, the most important thing is not the ability to use computers well, but motivation. This is because automated education is provided at a low unit price and is almost free, and in such an environment, how much students learn is determined by their will/curiosity/desire. In the past, there were understandable reasons for not receiving education, such as “because their family was poor,” but in the world in which today’s generation is growing up, there will be no other reason than “because they are lazy.” And what is even more important is self-control. Computers that have the ability to teach students in this way can also make students buy products and become addicted to games. In fact, all technologies used in education are technologies developed/distributed for entertainment purposes, so there is no technology that only teaches. Learning with computers always requires the ability to resist such temptations.

How to know if you have a sense of physics – part1

By James H. Choi

http://Column.SabioAcademy.com

Source URL

Students who are good at physics have studied hard, but they also have an innate understanding of physical phenomena. Nowadays, studies have concluded that even newborns as young as a few months old understand gravity. For example, if a ball rolling on a desk leaves the desk and doesn’t fall to the floor, a newborn will watch it for a while longer. They notice that something is wrong.

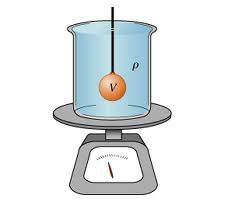

I think I’m one of those people who intuitively understands physical phenomena. One example I remember is a question posed by my teacher in first grade physics class. In the situation on the right, the question was, “What happens to the scale if you put the orange weight in the water or not?

It seemed illogical to me that there would be no difference between putting the weight in the water and not putting it in the water. It seemed like it had to make a difference because it was in the water. However, I also realized that if the weight touched the bottom of the beaker, the entire weight would show up on the scale, but if it floated in the middle, it would show up lighter. But I also realized that the lighter weight had to be something logical and mathematically calculable, so I raised my hand and said, “It goes up by the weight of the water in the ball’s volume.” The teacher was right. The teacher said I was right. I hadn’t learned about buoyancy until then. It was just a guess that I made while trying to find a number that was greater than zero, lighter than the weight itself, and that I could calculate using the materials I had. I think I became addicted to the exhilaration of making that guess. Maybe that anecdote was the first step that led me to major in physics.

I always learned physics this way. Whenever I learned a concept, I would subconsciously roll a “tongbap (gut feeling)” and if my guess was correct, I would say with a pleasant feeling, “Then that means…” If I was wrong, I would nod my head deeply in understanding, and if I was right, my eyes would widen in “wonder” and I would learn with even more interest, and my “tongbap (gut feeling)” would be re-tuned, and I would try to grasp the principle more precisely the next time. Physics formulas were not memorized, but were a tool to codify my intuition, just as you can guess a length with your eyes, but use a ruler to measure the exact number. Whenever I look at a formula, I have a habit of looking for the denominator to go to zero and the square root to be negative. It’s the mechanical equivalent of tearing apart a machine to see if it’s broken, but it’s a very useful habit in physics. (If you look at Einstein’s formula for relativity with this eye, you can see at a glance that you can’t go faster than the speed of light without anyone telling you, and that momentum explodes to infinity once you reach the speed of light.)

There are two types of students who struggle with physics: those who are weak in math and cannot translate their intuition into formulas and formulas into intuition. This is a classic case of “physics is fun, but my grades are low”, as is the case of someone who struggles in a subject they are good at because they are not good at English. Learning math will take care of itself, and most of the time, they discover this after the fact.

The other type is when you don’t have a physics intuition. They think that physics is a series of esoteric formulas and that studying physics is about learning how and where to substitute what into which formula. However, physics is a subject that cannot be avoided from the start if you are not good at it. Just like learning English, if you are not good at it, you need to learn it better and earlier and bring it up to a certain level in high school. It’s like teaching English at a young age, because it’s an inevitable subject if you want to be a leader in the modern economy.

But how can you tell if someone is the type of person who has an intuitive understanding of physics or not? How can I take the above physics problem and see if I can solve it intuitively? Here’s an opportunity to experiment. The video below is just a video of what you see without any special effects. If you watch this video and can’t figure out how it was done by the end, you don’t have an intuition for physics. Just as a child born with a weak body should learn to exercise from an early age to normalize his physical strength, a student who cannot figure out how to shoot this video should learn to do science from an early age in the form of playing with it.

The faster you can figure out how the video was shot, the stronger your intuition is, but I don’t know how much intuition you need to figure it out in a few seconds. I figured out how it was shot by watching the first person walking, so I guess it took me about 5 seconds.

If you have a child in elementary or middle school, this is a fun and free way to measure your child’s physical aptitude.

The Importance of Scientific Research in College Admissions

By James H. Choi

http://Column.SabioAcademy.com

Source URL

Note: This article was originally published in the Chicago JoongAng Ilbo in 2015.

A few days ago, I attended a celebratory dinner for a student who had been accepted early to her dream university. This student is a senior at a prestigious boarding school on the East Coast and attributed her early admission to her scientific research experience. At first, I dismissed this as another typical “self-analysis of admission reasons.”

However, during dinner, I learned something surprising: other students with similar or even stronger credentials had been either rejected or deferred, while this particular student was the only one to be accepted early. One notable difference: scientific research experience.

The student’s extracurriculars also stood out—unlike many other applicants, she played an instrument that wasn’t violin, piano, or cello, and participated in activities outside the usual tennis or missionary work. But the consensus at the table was that the key differentiator was her scientific research. The strongest evidence? The university specifically mentioned her research in the acceptance letter and even offered to connect her with faculty members conducting similar studies.

As word spread, the importance of scientific research became apparent among other students still awaiting decisions. Even during our dinner, the student received multiple text messages asking, “Where did you find your research mentor?” It was clear that this realization was sinking in across her peer group.

If all of this is true, an important question arises:

Why does scientific research play such a crucial role in college admissions?

To understand this, we need to consider what top universities truly seek in applicants. If you believe they are simply looking for academically gifted students, think again. What they actually want are students with the potential to make a significant impact in the future—individuals who will go on to achieve great things, bring prestige to the university, and, ultimately, become major donors.

This might sound cynical, but it’s no different from how politicians prioritize winning elections. Just as politicians must win elections to implement their policies, universities rely on major donors to fund scholarships, attract top faculty, support groundbreaking research, and ultimately maintain their elite status.

In my opinion, this explains why Asian students often face an uphill battle in elite college admissions. The donor-to-beneficiary ratio matters. Universities don’t just consider academic excellence; they also calculate the long-term financial contributions their graduates are likely to make. If historical donation patterns suggest that a particular group contributes less in the long run, it makes sense (from a university’s perspective) to limit admissions from that group.

This is why some Asian applicants feel unfairly rejected, saying, “But I got a perfect SAT score!” However, if universities were to fill their campuses with students who only focus on academic achievement and lack long-term donor potential, they would face financial challenges in the future.

So, how do universities identify students who are not only academically strong but also future industry leaders and potential donors?

There are certain key traits they look for:

- Proactive initiative – They don’t just complete assigned work but actively seek out new challenges.

- Self-driven learning – They acquire knowledge independently rather than relying solely on school instruction.

- Fearlessness in tackling unsolved problems – They embrace challenges that others shy away from.

- Perseverance – They don’t give up until they solve the problem at hand.

- Innovation and adaptability – They stay ahead of technological trends and apply them productively.

For admissions officers, scientific research is one of the clearest ways to identify students with these qualities.

Why? Because if students lack these traits, they simply won’t be able to complete meaningful research.

That’s why top universities value research experience so highly.

And importantly, winning competitions is not a prerequisite. The student in our story received her early acceptance before the results of the Intel STS competition were even announced.

Advice for Future Applicants

Today, there is an overflow of students who are “obedient, well-behaved, and good at standardized tests.”

However, this signals the mindset of a lifelong employee, not a future industry leader.

If you aspire to attend an elite university, it is not enough to present yourself as a great beneficiary of education—you must also demonstrate the potential to become a significant contributor and benefactor in the future.

This approach is not just beneficial for college admissions; it is also critical for adapting to the rapidly evolving social and economic landscape.

And one of the best ways to develop these essential skills? Engage in meaningful scientific research.

As fields like AI, biotechnology, and sustainability become more critical, students with hands-on research experience in these areas will be even more competitive in admissions.

So whether your goal is college acceptance or long-term career success, developing skills in problem-solving, independent learning, and innovation will be crucial. And there’s no better way to cultivate these skills than by conducting real-world scientific research.